Dieter Scholz

Red Stars and Text Clouds. Brigitte Waldach’s Spatial Drawings on the RAF.

Disturbed and fascinated, spellbound and irritated, observers stand before the works of Brigitte Waldach like the figures of her images. For years now, her drawings have reached beyond the page and extended into the space. The inclusion of sound and language creates a temporal structure, causing the multidimensional arrangements to seem like stages permeated by reality and imagination. By moving through image and text, the observer becomes part of the performance.

The colour red functions as a signal – and with its deep carmine shade – less for love or eroticism than blood. Indeed, Brigitte Waldach confirms that murder mystery and horror films influenced her choice of colour. Her work cycle sichtung rot [“searching red”] has been ongoing since 2002 and comprises drawings, silk screens, slides/foils, photographs, films and installations.

In working with the colour red it was inevitable that the artist would also confront its revolutionary symbolism. Inspired by the natural phenomena of sunrise and sunset, the 19th century labour movement rallied beneath the red flag, and via the Russian Bolsheviks and their Red Army the symbolic tradition made its way to the West German Red Army Faction (RAF).

I

Published on May 22, 1970, the manifesto Build Up the Red Army is considered to be the first public statement by the militant group initially described by the media as the “Baader-Mahler-Meinhof-Group”. This was followed in April 1971 by the 14-page white paper Red Army Faction: The Concept of the Urban Guerilla. Their signet was a five-pointed star crossed by a machine gun aimed towards the right.

Graphic designer Holm von Czettritz once explained that he had been asked to rework the logo by Andreas Baader, who lived in concealment until his arrest on June 1, 1972. As a “brand creator” Czettritz maintained that the imperfect, stencil-like image was much better suited to embody the RAF “corporate identity.”

The members’ media savvy was highly developed. The images of Hanns-Martin Schleyer, President of the German Employers’ Association, who was abducted on September 5, 1977, function as contemporary emblems. The RAF logo as title or inscriptio, the portrayal of the person as image (pictura) and underneath the explanatory text (subscriptio) – in this case the words “Prisoner of the RAF” and the respective date. Publicized as both photographs and film, the orchestration was transmitted over televisions into the living rooms of the Federal Republic of Germany.

The history of the RAF culminated in October 1977 with the foiled attempt to effect the release of imprisoned RAF members by hijacking an airplane in Mogadishu; when RAF protagonists Andreas Baader, Gudrun Ensslin and Jan-Carl Raspe were found dead in their prison cells at Stuttgart-Stammheim; and when the Employers’ Association President was murdered in retaliation.

Anyone who was politically socialized in the 1970s was influenced by these events. Two films at the time captured the nation’s zeitgeist. Germany in Autumn, a group production by 11 directors consisting of short documentaries as well as fiction films, premiered in February 1978. The film title gave a name to the past events that associated both melancholy and mourning with the natural cycle of destruction. A corresponding frequent expression of the times was the term “late capitalist state”.

Shortly thereafter, a feature film summed up the decade perfectly. “Margarethe von Trotta’s film Die bleierne Zeit was of great importance to me,” explains Brigitte Waldach. “It influenced my political thought more than my childhood memories of the media reports from autumn 1977.” At the time the artist was only 11 years old; she was 15 when she saw the film.

Director Margarethe von Trotta took her title from an unfinished poem by Friedrich Hölderlin to characterize the rigid and authoritarian climate of the 1950s in which the future RAF members were raised. By the time the film was awarded the Golden Lion at the Venice Film Festival, the term had become a part of common speech, with the double meaning of “bleierne” [“leaden”] pointing both to the paralysis and stagnation of society as well as to the bullets used and received by the extremist RAF.

The film Die bleierne Zeit portrays in the protagonists Juliane and Marianne the lives of Christiane and Gudrun Ensslin. Children of an art-loving protestant minister in Swabia (southern Germany), both sisters became involved with the student protest movement, but then went separate ways. As a journalist Christiane championed the women’s rights movement and co-founded the feminist magazine Emma. Gudrun trained as an elementary school teacher, started a dissertation on writer Hans Henny Jahnn and looked to poet Else Lasker-Schüler as a role model. Between 1967 and 1968 she turned to militant activism and was jailed for her participation in the arson of two Frankfurt department stores.

In 1981, Christiane Ensslin was actively involved in the production of Margarethe von Trotta’s film and together with her brother Gottfried in 2005 published the letters that Gudrun Ensslin wrote to them while in prison from 1972 to 1973.

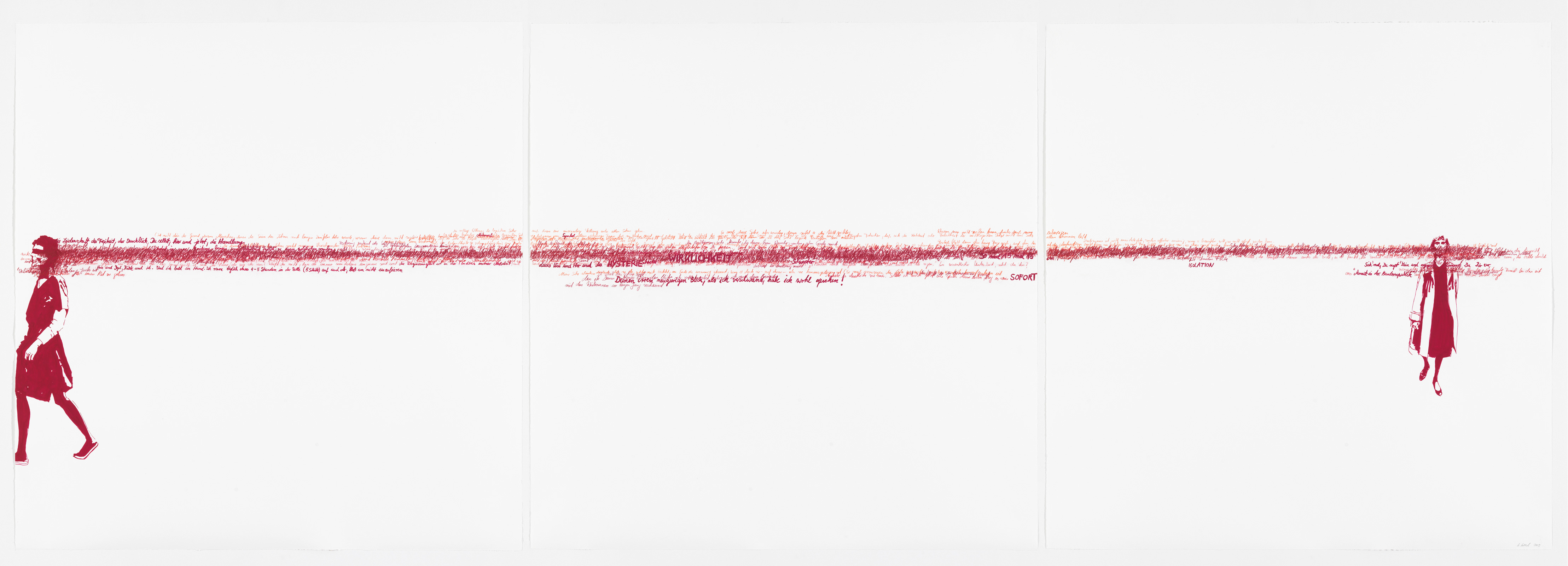

Gudrun and Christiane

This book became a critical source for Brigitte Waldach, not only for the text, but also for its central imagery. Two photographs from the book are the basis for her image of Gudrun Ensslin in profile and that of Christiane Ensslin walking towards the observer. In a large format, three-part drawing a maximum distance between the two sisters exemplifies their disparity; text is the element that binds them. A band of communication runs from Gudrun to Christiane, not merely because of the western habitude of writing from left to right, but also because only the letters of Gudrun were available, while the letters Christiane sent to the prison “have disappeared and their content are reflected only in Gudrun’s answers.”

Thus it is Gudrun Ensslin who speaks in the picture. Brigitte Waldach made two modifications to the original. A blindfold that might otherwise suggest blindness points here to Gudrun’s solitary confinement, during which the prisoner had no eye contact with other prisoners, even during recess in the prison yard. Also, the image of her walking is cut off at the drawing’s edge, which can be seen as her abandonment of the social space. The prison-garbed subject has turned her back to her sister dressed in everyday civilian clothing, and is in relentless pursuit of the left.

The sentences Gudrun Ensslin addressed to her sister function on various levels. Directly overhead reads “The passion of freedom, the insight, you yourself, here and now, the action” – formulations of fulfilment in an attempt to politically persuade her younger sister. Somewhat lower in the image, the question “Where does it come from” references the publication of excerpts from Gudrun’s letters to Christiane in the Frankfurter Rundschau newspaper. The author can imagine that information was passed through the censor, yet also suspects her sister of being naive and warns: “Don’t you know that they are always at least inaccurate, and inaccuracy is most often tailored.” Finally at the bottom of the picture is evidence of her emotional state: “Hare and hedgehog, me and the cold. And I’ll soon be a dog. Every day I run 4 to 5 hours back and forth in the cell (5 steps) just so as not to freeze.”

Gudrun Ensslin’s textual output oscillates between personal emotion, precise analysis and political agitation, and in Waldach’s illustrative representation the levels overlap into a zone of illegibility. In the triptych’s middle part consisting purely of text, one sentence lower down in the image receives particular emphasis: “I did indeed see your insanely curious look as I disappeared.” This is surrounded by a somewhat later paraphrase: “that I did indeed notice your look burning in curiosity, when after a visit I disappeared with the guard down the long hallway.” In this middle part, the gaze and disappearing are present only in text. On the triptych’s left panel, Gudrun’s figure is depicted disappearing at far left; on the right panel, the gaze is positioned on the right, where Christiane Ensslin can look out above the edges of the text. “Look here”, stands expressively beneath her, “You say that you feel ‘small and aggressive’ when the gate is closed – do you know that this could be the most concise expression for what Poverty in the Federal Republic of Germany states across who knows how many pages?” The subsequent passage in the original letter states: “This is what happens when before one’s very eyes one is declassed, denounced, impossibly treated and is forced to watch this, as mentioned, completely impotent”. By placing the text cloud over the figure’s mouth, Brigitte Waldach visualizes the sense of stifling described in the text. The word “Durchblick” [“view”] is printed near Gudrun, but her eyes are covered. Christiane on the other hand is able to stand witness to the events with eyes open, literally.

The three-part drawing Gudrun und Christiane [“Gudrun and Christiane”] was realized in 2009 and continues motifs that Brigitte Waldach developed in the year prior to the exhibition Drei Farben – ROT [“Three Colours – RED”] in Potsdam. As a final part of an exhibition trilogy inspired by the French tricolour and the tenets of the French Revolution, the notion of “fraternity” was the point of departure for the show’s curatorial concept. Brigitte Waldach used the occasion to search for “sorority” within the framework of revolutionary politics.

For the exhibition, Brigitte Waldach drew directly on the walls, floor and ceiling of a room on the top floor of Villa Kellermann in Potsdam “Passages from the letters to Christiane penetrate the hermetic exhibition space in a deep red. The red tones differentiate the letter fragments from the books (in light red) that Gudrun Ensslin had her sister Christiane bring her in prison. The list of books she requested included literary, philosophical as well as political texts, including Friedrich Engels’ The Origin of Family, Franz Kafka’s The Hunger Artist, poems by Ezra Pound, dramas by Jean Genet and the Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus by Ludwig Wittgenstein.” Ten loudspeakers were mounted on the walls and connected with red cables, creating lines of perspective throughout the room. The technical aspect of the work was integrated into its aesthetics. “At first glance, one could imagine being at the scene of a crime,” comments one reviewer. “Yet what seems to be blood spatters in the white room proves to be text: quotes […] overlap like the voices whispering from the loudspeakers. A delicately drawn woman glides between them, a red star.”

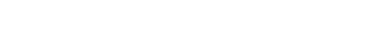

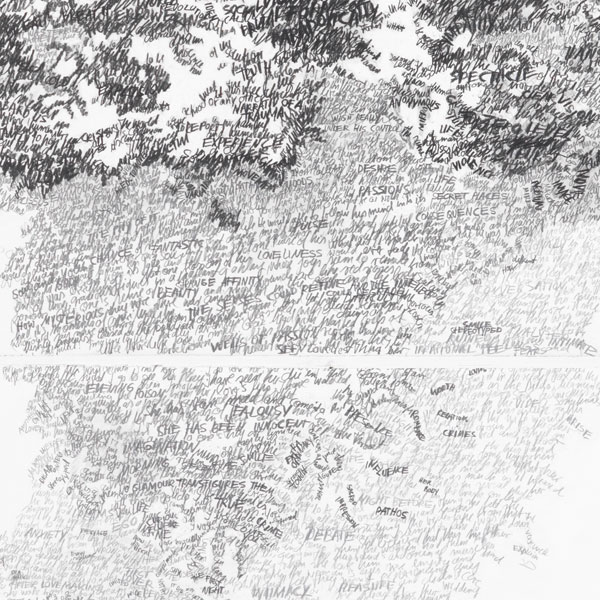

The star boldly suggests unambiguity. This, however, is offset by the “text clouds” – the term used by the artist to describe her concentrated patches of writing. The wavering letters are characteristic of her RAF drawings. The uncertainty this might evoke is absolutely intentional. According to the artist, a loss of equilibrium is also symptomatic of solitary confinement. In addition to the three dimensional variation Gudrun und Christiane II [“Gudrun and Christiane II”] conceived for Art Brussels the artist realized the triptych Deutscher Herbst [“German Autumn”] that was shown in the same year at art forum berlin. Here, the figures move between tree trunks and printed beside a red star in uppercase letters are the words “DER MYTHOS IST EINE MASCHINE” [“THE MYTH IS A MACHINE”].

The term “myth” links to a discussion that dominated German media in summer 2003. Kunst-Werke Institute for Contemporary Art in Berlin planned a project with the working title “Mythos RAF.” A quarter-century after the “German Autumn” and five years after the written voluntary dissolution of the RAF, today’s “younger generation” – only familiar with the “ghosts of Baader, Meinhof and Ensslin” as quotations from “random artifacts from popular culture,” – should be informed of the historical context and media echo of the RAF. Inadvertently, the massive knee-jerk reaction to the planned exhibition made quite clear just how much “the RAF phenomenon had been personalized, then dehistoricized and thereby mythified. Felix Ensslin was one of the curators of the exhibition, which was finally realized in 2005 under the title Zur Vorstellung des Terrors [Regarding Terror: The RAF Exhibition]. In her installation in Potsdam, Brigitte Waldach allows her text clouds to dissipate with Gudrun Ensslin’s request for photographs of Andreas Baader and “in addition maybe two of Felix. Felix isn’t an RAF member. Felix is my son”.

Famous (diptych), 2009

Gouache, pigment pen on handmade paper

195 × 280 cm

Private collection, Deutschland

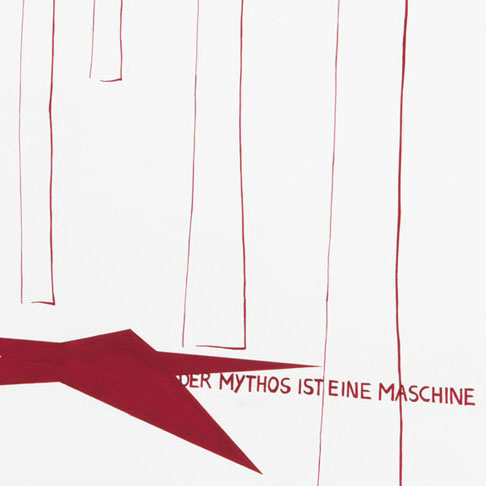

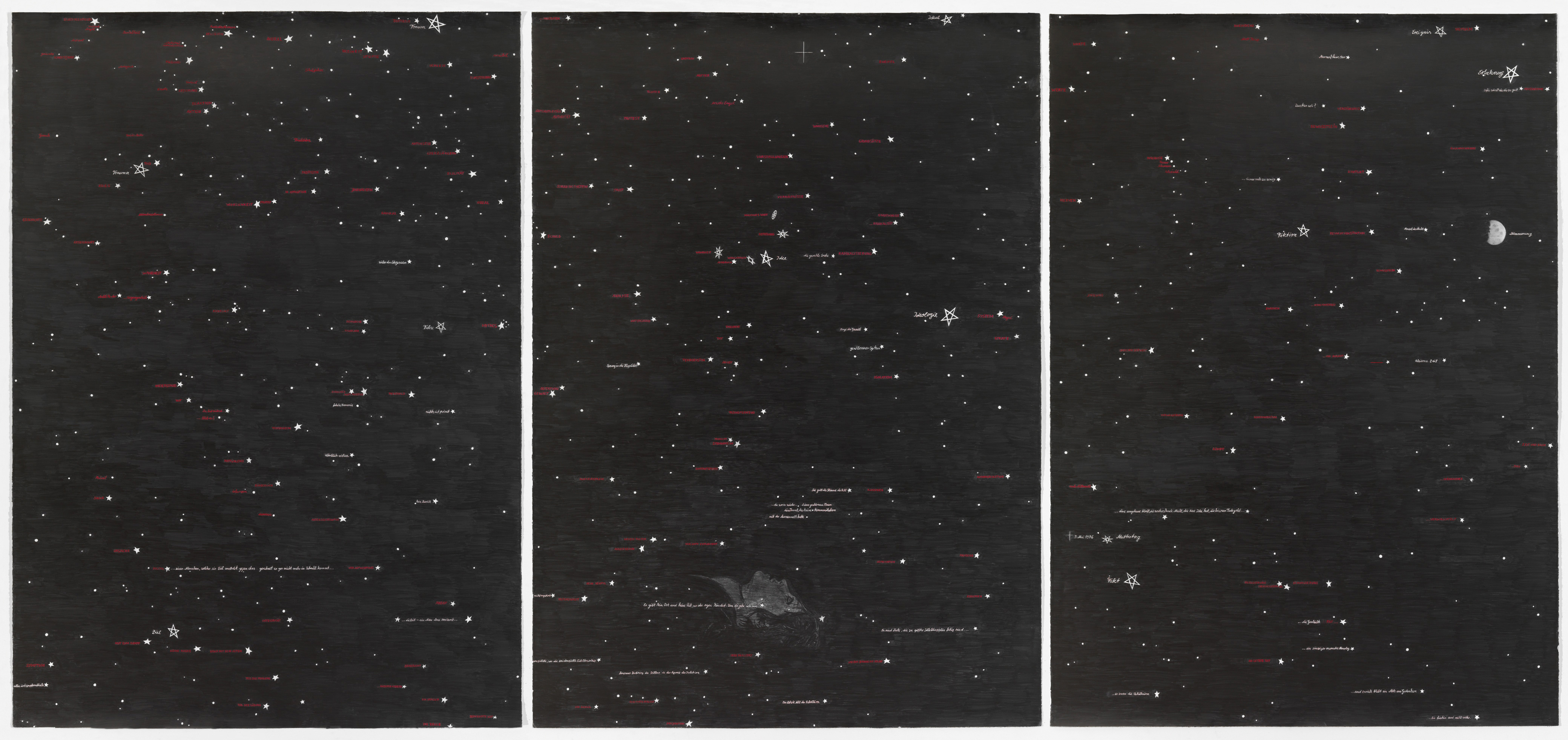

Tief im versenktem Raum, 2010

Gouache, pigment pen on handmade paper

146 × 140 cm

Private collection, Berlin

Deutscher Herbst I (German Autumn, triptych), 2009

Gouache, pigment pen on handmade paper

185 × 420 cm

Private collection, Denmark

Deutscher Herbst II (German Autumn, diptych), 2010

Gouache, pigment pen on handmade paper

185 × 420 cm

Collection Alison und Peter W. Klein, Germany

Gudrun und Christiane (triptych), 2009

Gouache, pigment pen on handmade paper

146 × 420 cm

Fondation Paris / Denlins

Muttertag – 9. Mai 1976 (Mother’s Day, triptych), 2014

Graphite, gouache, pigment pen on handmade paper

185 × 420 cm

Collection Alison und Peter W. Klein, Germany

Die Welle – Moby Dick (The Wave, triptych), 2011

Gouache, pigment pen on handmade paper

185 × 420 cm